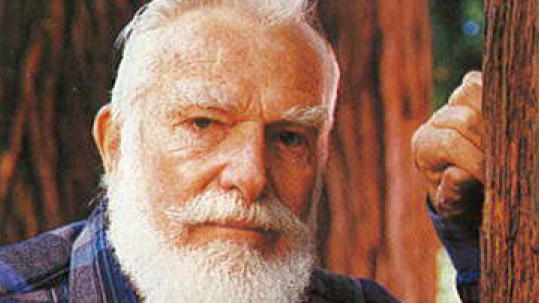

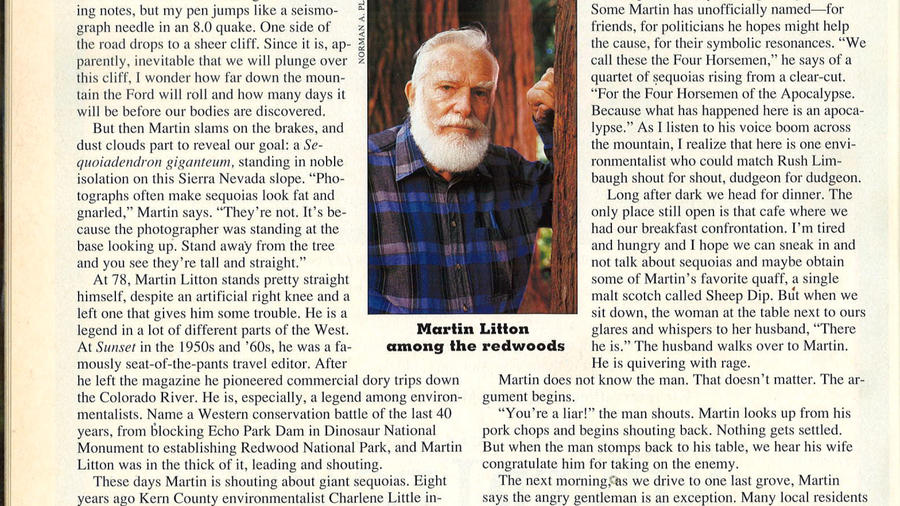

In 1995, Litton brought current deputy travel editor Peter Fish on a treacherous adventure to see the sequoias. At the time, 78-year-old Litton was pushing for a sequoia reserve after witnessing the logging that took place in Sequoia National Forest. Fish describes him as a “seat-of-the-pants travel editor.”

AT LAST A REDWOOD NATIONAL PARK IS IN THE MAKING. WHAT SORT OF PARK WILL IT BE?by Martin Litton

The idea of a national park in California’s coast redwoods, discussed for more than half a century, is now the subject of a specific proposal before Congress

Last October, four congressmen—Phillip Burton and Jeffery Cohelan of California, Henry Reuss of Wisconsin, and John Saylor of Pennsylvania—introduced four identical bills calling for the establishment of a national park in the Redwood Creek watershed. And early this year precisely the same area was specified in redwood national park bills introduced by congressmen Edward Roybal of California, James Scheuer of New York, Sidney Yates of Illinois, David King of Utah, Morris Udall of Arizona, William Moorhead of Pennsylvania, and John Dingell and Billie Farnum of Michigan.

In one sense the job of planning a redwood national park has become easier as the opportunities for choice of location have diminished. The framers of the proposed legislation consider that there is no longer any choice. The area they propose for the national park status includes the lower end of the watershed of Redwood Creek, which is now in private ownership, and 18 miles of wide, sandy ocean beach.

The park would bring protection to herds of Roosevelt elk that do not enjoy the sanctuary of the present Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park and are annually subject to killing by hunters. Along Redwood Creek, the park would provide a protected environment for what are believed to be the world’s tallest trees, first measured in 1964.

The park proposal reflects the results of a year-long National Park Service study of the redwood country, published in booklet form last year.

If you got to explore the proposed national park area for yourself—and you can do so this month, using the map on this page as a guide—do not expect to find yourself wandering for mile after mile through a towering redwood forest primeval. There no longer is any such thing. The remaining redwood stands everywhere are fragmentary, interspersed with areas of stumps and young growth, and with land converted to non-forest uses. The proposed national park area is no exception.

But you will encounter beauty. You can make your headquarters in a good motel in Orick and fan out from there.

In cut-over sections, you may encounter unrepaired road washouts from the winter’s rains, but if you stay on the public routes you should have no trouble.

Except for the area of Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, the timberland proposed for inclusion in the national park is privately owned. You can pass freely through this land on three public roads—U.S. Highway 101, the Bald Hills Road, and the county road to Gold Bluffs beach—but use of private logging roads in the region is always restricted to some extent, and sometimes forbidden altogether.

“World’s tallest trees.” The three tallest trees known to be standing and also the sixth tallest, are all in one small bend of Redwood Creek. The tallest of these has been measured at 367.8 feet, and the others reach almost the same height. The grove is owned by the Arcata Redwood Company, which began logging operations nearby just last year, but the access road runs through property of the Georgia-Pacific Company on the other side of the creek. This winter, landslides in the logged-off area through which the road passes damaged it severely, and the time when it may be open to visitors remains in doubt. On weekdays it is used by logging trucks. If you are in the area on a weekend and want to visit the tallest redwoods, first obtain permission from one of the lumber companies. Georgia-Pacific has a mill at Big Lagoon, and Arcata Redwood Company has two near Orick (see map).

Even at the “tallest trees” grove, you will not get the full impression of the forest majesty still remaining elsewhere on Redwood Creek and on Little Lost Man, Lost Man, and Bridge creeks, because of the vicinity. If you would like to see redwood forest typical of what the national park would preserve, walk the improved trails in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park. For details, see Forest walking and forest camping, in the September 1963 Sunset.

Bold Hills Road. This excellent paved road goes east from U.S. 101 a mile north of Orick and stays on the ridge for 18 miles, giving frequent sweeping views across the valley of Redwood Creek and also out over the Klamath River country to the east. In addition to the natural openings provided by the grassy balds or “prairies” along the ridgetop, there are the ceaselessly widening ones where the forest is being “daylighted” by cutting.

In the first mile, as you wind up the steepest part of the road, you’ll come to several turnouts where you can park and look south, straight up Redwood Creek.

Before you get to the top of the hill, giant trees hedge you in on the left. You are passing the edge of the unbroken forest that mantles the headwaters and most of the course of Little Lost Man Creek—the only perennial stream in the redwoods, inside or outside of any park, with all of its headwaters still in the virgin forest.

The high meadows (balds) farther along the road are fine spots for picnics on pleasant days. As you look west, the sloping foreground woods are splendid, and you can see the ocean (or its fog bank) beyond the farthest ridges.

Gold Bluffs beach. A mile south of the Prairie Creek Fish Hatchery (which you can visit), a graded road goes west, along the south side of the grounds of Moseley’s Motel. It appears to be a driveway to the Arcata Redwood Company’s Mill B, but it is a public road and it continues past the mill, over a low ridge, and on down to the beach. A primitive road goes north on the beach, along the base of the beautiful Gold Bluffs, to renowned Fern Canyon, where sheer walls 30 to 50 feet high are clothed thickly with five-finger ferns.

Shortly after you pass the sawmill, you will observe one of the reasons for haste in establishing the national park. Where only two years ago there was majestic redwood forest, now there are hundreds of acres without a single tree.

Along the beach you can expect to see Roosevelt (sometimes called Olympic) elk. They will not run from your car, and they may not run from you, but it is not safe to approach them closely on foot.

Surf-fishing is good, and you should allow an hour for the stroll into Fern Canyon.